The word on the street is that Johannesburg, South Africa is a place of villains and cruelty. I had heard multiple warnings that you would be car-jacked in Johannesburg if you were foolish enough to stop your car at a red light. “Johannesburg has a higher crime rate than Iraq,” one Australian friend of mine warned me. My reading pointed me in another direction.

Nelson Mandela’s autobiography, “A Long Walk to Freedom” affected me deeply. He spent much of his life in Johannesburg as a lawyer arguing anti-Apartheid cases. He painted a lovely picture of South Africa as a “Rainbow Nation” where forgiveness dominated over the violent history. Mandela gave me the impression that South Africa is synonymous with triumph over adversity. I’d have to see for myself.

All reading aside, I had an understandable level of trepidation as I packed for a day trip into Soweto. Soweto (or the South Western Township) is a vast neighborhood of people, many of whom live at a level of poverty I have never experienced or can really understand. This area was the epicenter of the anti-apartheid rebellion which swept across South Africa in the late 1970?s. AIDS mortality rates are the highest in the world in South Africa. The movie about segregated aliens called Sector 9, was filmed here and inspired by the social architecture of Soweto during Apartheid.

On the way from our rich, predominately white neighborhood, we made a detour to see the Soccer City Stadium. This mammoth building can manage 90,000 and was built exclusively for the FIFA World Cup. It is massive and mesmerizing. A swath of rich African sunset colors have been painted on the enormous panels that wrap around the building. The panels are like tiny pixels in an enormous digital collage which makes up the exterior of Soccer City. The building’s form is inspired by the African Calabash which is a natural gourd that is used to share food and the African fermented milk booze. Over the next 6 weeks this triumphant building will be the site of the most important sport competition in the world.

South Africa was under the gaze of the world. “Will they be ready?” was the common question. This was to be the first FIFA World Cup to be held on the continent of Africa. Will Africa be able to pull this immense undertaking off? One could entertain doubts while standing in front of Soccer City two weeks before the games begin and construction isn’t finished. Hundreds of workers were milling around the structure like ants. Those working the landscaping and side walks near the front smiled and worked calmly while those far off on the building were so minuscule in comparison to their structure that one couldn’t tell if they were working or chilling.

In South Africa there are neighborhoods called townships. Townships are predominately black neighborhoods that were either historically where the blacks chose to live, or were drawn up in the early 20th century by the Apartheid Regime. Drawn up like: “the blacks over there, the coloreds over there and us whites here.” Apartheid is an Afrikaans word meaning separate and apartheid wanted a separate society. Much like “separate but equal,” which we had in the USA-South, but Apartheid was even less focused on equality.

There are many parallels to the civil rights movement of the United States and that of Africa. In both the whites tried to choke economic growth and social development from the blacks. In both instances the whites would implement demeaning policies aimed at suppressing the self confidence in the black population. In my opinion, the large difference between ZA and USA is that in the USA the whites are the majority. In South Africa the whites are the minority. The potential for power struggle created an understandable level of fear in the dominate white group. Besides, in South Africa the whites aren’t even a unified group.

Afrikaans is a Dutch based language that has developed it’s own style and soul that is truly African. Afrikaans people are white, but they are entirely African. They have their own history and allegiances to Boer farming roots and Paul Kruger. The whites that have more British influence hold allegiances to the Queen and Cecil Rhodes. As a rule, they don’t speak Afrikaans and they have a more British view of human rights. Unification of the Cape of Good Hope, the Orange Free State (Boer), the Natal and the Transvaal was a dream of Rhodes. Rhodes dreamed of seeing a unified country and this idea led to violent times. None-the-less, South Africa was unified through the South Africa Act of 1909. (there was a very long coming and complex agreement that was reached here. Books can we written about the complexities of this act.) 40 years later, Apartheid governance took over.

The Apartheid governance developed a complex and perplexing system of laws to separate the different races based on color. There was no separation of races based on ethnic understanding. The Zulu and the Xhosa are both blacks but they are far from homogenous. Afrikaans and old British white folks have their own feelings of distrust towards each other. The coloreds (Indian, Malay, black and white mix) are also a interesting mix of people. None-the-less, Apartheid Government says: “blacks over here, whites here and coloreds here” and that’s how it went. Now, more than 100 years later we are touring around to see how it all has played out.

We left Soccer City for Soweto driving fast in our big white VW van.

Johannesburg has a highway system as imposing as that of Los Angeles, California. A significant difference in South Africa; the lines for traffic are more ideas than rules. When traffic gets bad the 4×4 trucks go off the road and up on the mud dividers to get ahead of the rest. Anywhere where your wheels can carry you is fair game on the South African roads. People swerve inside the orange construction cones to get ahead of those foolish enough to line up. The construction for the World Cup was causing bizarre traffic jams.

This was the sort of traffic jam where, in California one keeps their window up and their head down. As I sat in the back of the car, I couldn’t help but feel that these cars full of Africans were all smiling and giving us thumbs up. Most seemed positive about the traffic and happy to just be moving. Sure, we were stuck but I got more thumbs up in that gnarly traffic jam than I do in a year of California driving.

We came up over some hill top and we were informed that this expansive swath of dwellings was Soweto. Soweto sprawls out as far as the eye can see. Over the far hills you see hills of Soweto in the distance. It’s a strange blend of government brick buildings and shanty towns constructed of tin roof material and whatever else could be produced.

Though many of the homes look as if they are built by an assembly line, many of the dull old run down government buildings have been remodeled into beautiful homes. They have gardens, fancy gates and car ports. Outside on the street people sell food under the cover of a tarp supported by a few poles for shade. Open air barbers cut peoples men and women’s hair down to the super popular buzz cut. “Surgery” was offered on signs all around, but we learned that these were simply pharmacies, not places to have surgery performed. The government buildings that have been converted into drinking establishments are called “shebeens.”

Down towards what feels like the center of Soweto, there are two huge power plant towers (like the nuclear power plant where Homer Simpson works). These massive structures have been all painted up triumphantly with a beautiful African mural. This old power plant is now a tourist attraction boasting the worlds 2nd highest bungee jump. It’s a stunning sight. The structure itself is and example of triumph over adversity. The power-plants used to spit out toxins in the middle of Soweto to produce power for the white folks living outside of Soweto.

As we drove through the center of the township I couldn’t help but notice all the smiles. Earlier that morning I expected to have an abrasive day of avoiding gangsters and panhandlers deep in the slums of aggressive Africa, but all I saw around me were smiles and people giving me the “thumbs up.”

Our first stop was at the Roman Catholic Church which was a center for solidarity against apartheid. The church does not match the vastness of the neighborhood to which it serves. It is a humble building, yet its history is remarkable.

Our guide showed us the bullet holes in the ceiling from when the security forces raided the church in response to the uprisings in the 1970?s. A broken marble mantle on the pulpit is left broken from the butt of a security force officer’s gun. The bullet holes and broken pieces of the church are left to remind the people of those violent times.

It was an amazing struggle. A black man during Apartheid had no basic human rights. Every Black was required to carry a book describing his work, his family and his travel permission. At any time and without due process, a police officer could demand to see a mans paperwork and move him or her along. The blacks weren’t allowed to own their houses or visit white areas without permission. The whites used the blacks as servants but never wanted them around afterwards.

Above the church was an exhibit of photos by Jurgen Schadeberg. Schadeberg documented Soweto during the youth uprisings. His black and white images of comfortable rich white folks juxtaposed with images of poverty stricken hungry black folks leave a lasting impression. He has images of dangerous looking Apartheid anti riot tanks, security forces beating protesters, protesters hiding from police and families crying.

Photo of Apartheid Poverty

We left the church. Despite all the friendly smiles, I must admit that I was nervous about being in the poorest place in one of the most dangerous countries in Africa. I’m about as white as Goldilocks. All of these images were of white people beating, enslaving and scaring the black people. Someone must hold a grudge? It was lunch time so our guide took us to a place down the road called Wandie’s for a traditional African meal. It was here that all my fear went away and I fell in love with Africa.

A pair of musicians surprised our group with finger snapping and singing as we walked through the door. One played guitar while the other drummed on whatever was near him all the while singing beautifully. The atmosphere was incredibly welcoming and warm. The food was rich, flavorful and exotic (though I’m no an of the tripe).

The musicians sang, played and spoke throughout our entire meal. They played the Lion King Song, Bob Marley Songs, and a host of African songs. We sang along, some danced and everyone was caught up in the comfort of the atmosphere. The musicians would speak briefly between songs about their culture. They described the South Africa that I read about in Mandela’s writing; a “Rainbow Nation” where everyone respects each others differences. Everything about lunch screamed rainbow nation, this was one of the greatest lunches of my life.

Our guide’s friend, Botha, a beautiful young Zulu girl danced along with the musicians and kept us entertained with her sassy humor. I asked her if she had to speak to Xhosa people in English due to the language barrier. She seemed surprised with my question and explained that she could speak all the languages of all the different tribes. “We grow up immersed in it,” she explained.

After lunch we drove to Nelson Mandela’s old home. As we drove down this street we learned that this was the only street in the world where two Nobel Peace Prize winners had both lived. Vilakazi Street. We passed Desmond Tutu’s house on the way to Mandela’s; both Nobel Peace Prize winners.

Nelson Mandela spoke fondly of his home at 8115 Vilakazi St, Orlando West Soweto. “It was the opposite of grand, but it was my firs true home of my own and I was mightily proud. A man is not a man until he has a house of his own.”

The history of the house is provided in the flyer. I’ve included the main history page of the flyer:

“The Mandela House at 8115 Orlando West, on the corner of Vilakazi and Ngakane Streets, Soweto, was built in 1945, as part of a Johannesburg City tender for new houses in Orlando. Nelson Mandela moved here in 1946 with his first wife, Evelyn Ntoko Mase and his first son. They divorced in 1957, and from 1958 he was joined in the house by his second wife, Nomzamo Winifred Madikizela (Winnie).

Nelson Mandela was to spend little time here in the ensuing years, as his role in struggle activities became all-consuming and he was forced underground (1961), living a life on the run until his arrest and imprisonment in 1962, and sentence to life imprisonment in 1964.

Outside the home of Nelson Mandela

Nelson Mandela returned to 8115 for a brief 11 days after his release from Robben Island in 1990, before finally moving to his present home in Houghton. Winnie Madikizela-Mandela, herself harassed by the security forces and imprisoned numerous times, lived in the house with her daughters until her own exile to Brandfort in 1977, where she remained under house arrest until 1986. The family continued to occupy the house until after Mandela was released from prison. The house was subsequently turned into a museum, with Nelson Mandela as a Founder Trustee of the controlling body, the Soweto Heritage Trust.”

This is the literature the pamphlet provides the visitor when entering the museum. Our guide informed us of a few details left out of the pamphlet: Nelson Mandela gave his home up to the Soweto Heritage Fund despite the fact that it cut his ex-wife’s source of income. His ex-wife, Winnie Mandela, had been using their old house as a shebeen. This upset Mandela because alcohol had played an important role in keeping the blacks under control during Apartheid. It took the power of a team of lawyers to have the house returned to Mandela. Mandela then gave the house to the Heritage Trust.

His home is just another old house built by the Apartheid government but this one is surrounded with modern walls to give it a modern museum feel. The exterior bricks are charred from firebombings while Winnie lived there. The interior of the building is packed full with fantastic trophies and letters of support from people and countries around the world. The house in very small and you can see it all in about 2 minutes, if you rush. If you take your time you could spend hours examining all the interesting gifts and print given to Mandela. I left with a profound sense of admiration.

Just down the road, we got to speak with the project manager for the Hector Peterson Museum. We learned that the place was built under contract for 40 million Rand. For 6 months management organized the Vilakazi area communities into rotating labor force that could build the museum. The production spent this time because they wanted to weave community involvement and the museum.

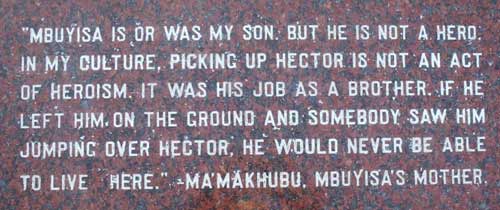

Hector Peterson was murdered at the age of 13 for rioting against Apartheid government in the youth revolutions of the late 1970?s. Peterson was unarmed and killed by fully armed and armored security forces under Apartheid directions to suppress black “upiddyness.”

The project manager was working to build this museum to recognize the sacrifice of the young man. He decided to award the building contact to a white building contractor. He told us the story of awarding the contract and it went something like this (I paraphrase):

“I sat the contractor down in my office and told him I chose his bid from all the others. I told him “I choose you” and the contractor remained silent for a moment, the he stood up and walked out the door. Two days later he called me for a meeting. He walked into my office, sat down and cried openly. The contractor explained that he had been a member of the Apartheid led security forces which were in Soweto on the day of Hector’s murder.”

This is stunning. One of the important officers in the Apartheid security force was used by the people of Soweto, as an integral tool in building the museum to honor a fallen revolutionary. It’s difficult to imagine a more triumphant perseverance of the South African people.

The project manager reported that the white contractor and the black community worked together smoothly throughout the whole building process. The project found a successful finish. He explained that the contractor was on side 7 days a week from beginning to end of the day. “His professionalism and dedication was moving,” he told us.

“No building tools or materials were lost to thieves throughout the whole process” he explained. The community had guarded the construction site without the need to hire a security company or erect a physical barrier around the site. This museum is a remarkable testament to the feeling of reconciliation that makes South Africa such a rich place to be.

Behind the museum is a memorial square dedicated to the youth sacrifice in Soweto and the youth league of the African National Congress (ANC). This square looks down a long street lined with trees, each tree planted by a different world leader or celebrity. The trees planted by memorable names such as Bill Clinton, Nelson Mandela, Alicia Keys, Don Hahn (producer of the Lion King), Desmond Tutu and a host of others.

The project manager wants this whole area to be developed into a big triangle “long walk to freedom.” One day a guest could walk all around the area to get a feel of the land and the people that make up the remarkable Soweto area.

Night had fallen by the time we left the Hector Peterson memorial. We got stuck in traffic for hours before we finally got back to our place. I sat up for hours despite the exhaustion from a long un-expected day. I couldn’t stop thinking of how foolishly afraid I was at the beginning of the day. Most of all, I was deeply inspired by the people of South Africa.

AYOBA!